________________

JAINA IMAGES

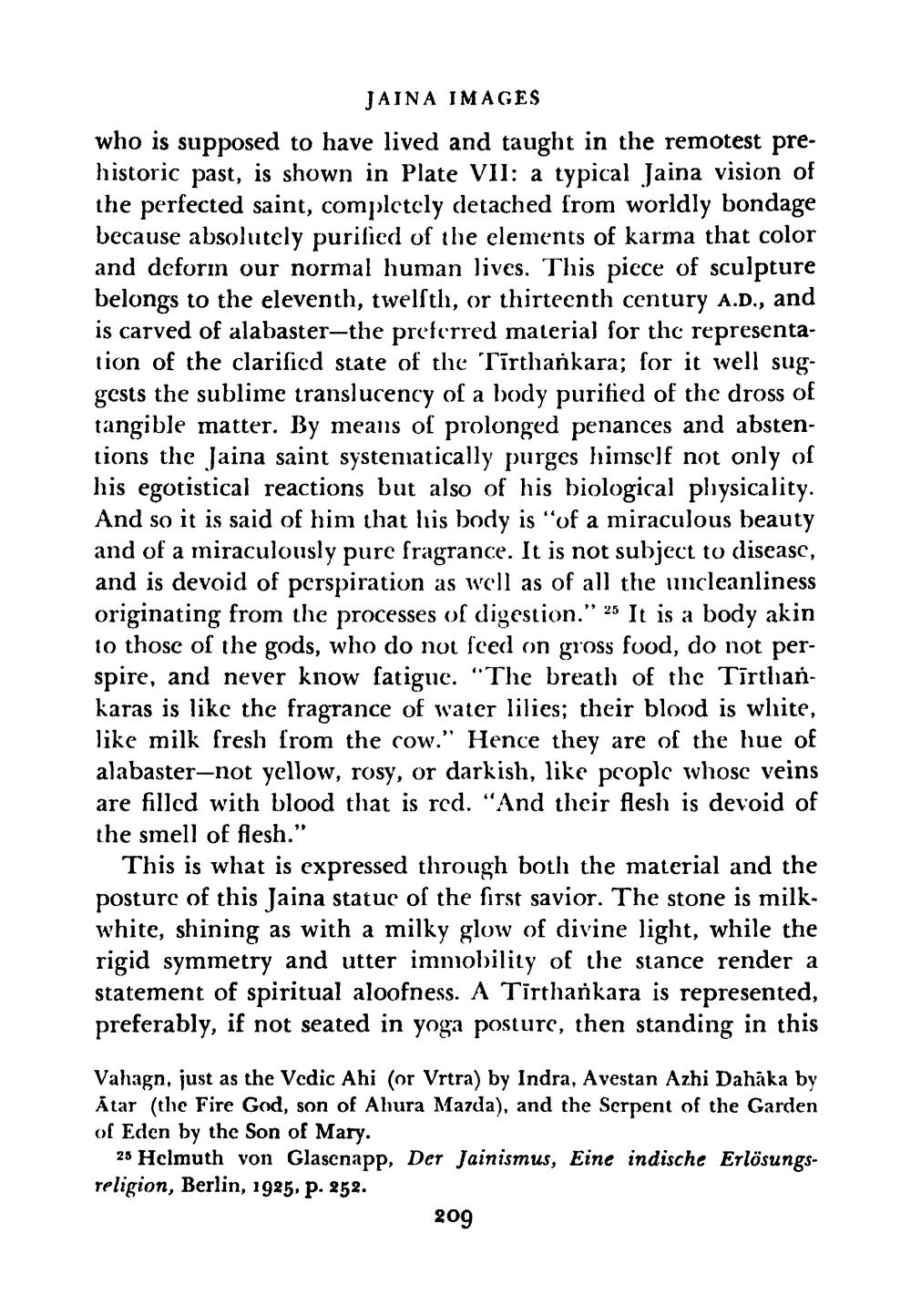

who is supposed to have lived and taught in the remotest prehistoric past, is shown in Plate VII: a typical Jaina vision of the perfected saint, completely detached from worldly bondage because absolutely purified of the elements of karma that color and deform our normal human lives. This piece of sculpture belongs to the eleventh, twelfthi, or thirteenth century A.D., and is carved of alabaster-the preferred material for the representation of the clarificd state of the Tirthankara; for it well suggests the sublime translucency of a body purified of the dross of tangible matter. By means of prolonged penances and abstentions the Jaina saint systematically purges himself not only of his egotistical reactions but also of his biological physicality. And so it is said of him that his body is "of a miraculous beauty and of a miraculously pure fragrance. It is not subject to discase, and is devoid of perspiration as well as of all the imcleanliness originating from the processes of digestion.” 25 It is a body akin 10 those of the gods, who do not feed on gross food, do not perspire, and never know fatigue. “The breath of the Tīrthankaras is like the fragrance of water lilies; their blood is white, like milk fresh from the cow." Hence they are of the hue of alabaster-not yellow, rosy, or darkish, like people whose veins are filled with blood that is red. “And their flesh is devoid of the smell of flesh."

This is what is expressed through both the material and the posture of this Jaina statue of the first savior. The stone is milkwhite, shining as with a milky glow of divine light, while the rigid symmetry and utter immobility of the stance render a statement of spiritual aloofness. A Tirtharkara is represented, preferably, if not seated in yoga posture, then standing in this

Vahagn, just as the Vedic Ahi (or Vrtra) by Indra, Avestan Azhi Dahāka by Ātar (the Fire God, son of Ahura Mazda), and the Serpent of the Garden of Eden by the Son of Mary.

25 Helmuth von Glasenapp, Der Jainismus, Eine indische Erlösungsreligion, Berlin, 1925, p. 252.

209